How the Linguistic Living Spaces Method Was Born

From Family Portraits to Spatial-Affective Worlds

Carola Koblitz

7/7/20255 min read

Introduction

The method now known as Linguistic Living Spaces (LLS) did not emerge as a ready-made research tool. Instead, it developed organically—from practice, from experimentation, and from continuous reflection on real research processes. Its origins lie in the project Family Language Policies in a Minority Context (Bautz, Habitzel, Hanisch, Koblitz & Lechner, 2022), carried out at the University of Vienna. In this study, our team introduced and tested the first version of what we then called the family language portrait, an adaptation and extension of Brigitta Busch’s (2021) individual linguistic portrait.

The project focused on two families living in multilingual minority regions—one in Vorarlberg (Austria) and one in Graubünden (Switzerland). Like many multilingual households, both families faced the everyday question of which languages to pass on to their children, how to manage their linguistic resources, and how to navigate the emotional and ideological terrain of multilingual parenting. Our goal was to understand these processes:

Which languages are used when, by whom, and in what situations? What social and emotional meanings shape these choices?

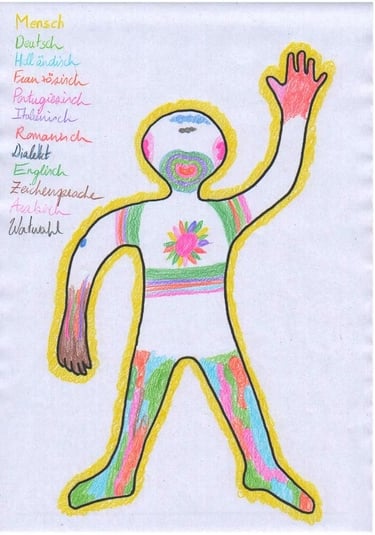

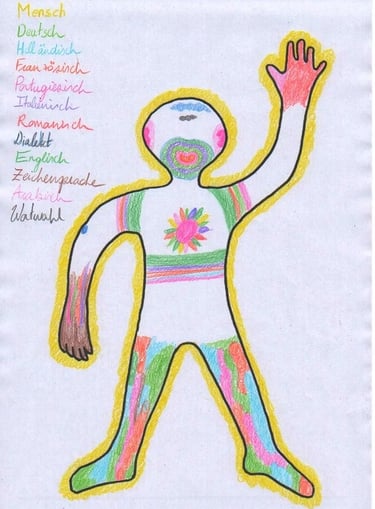

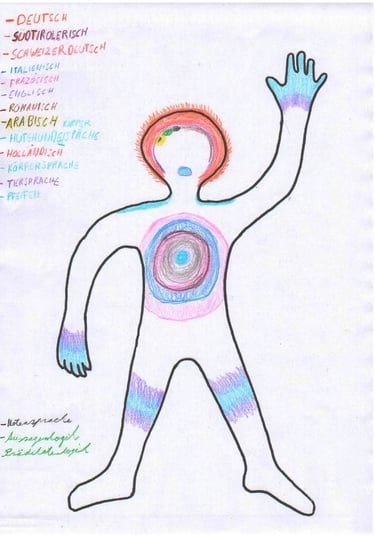

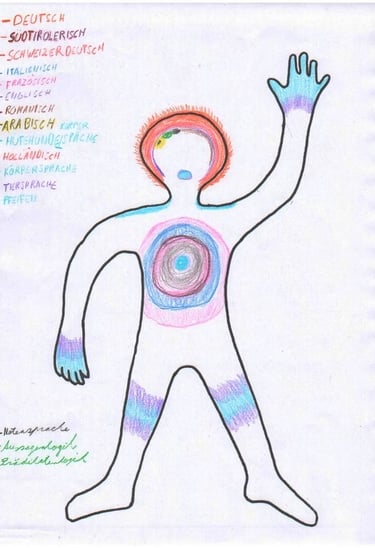

To explore these questions, we combined two visual approaches: the individual linguistic portrait (Busch, 2021) and our newly developed family language portrait. These visual tools were paired with guided narrative interviews (Helfferich, 2014) and qualitative content analysis (Rosenthal, 2014). Each adult participant—and, in one family, even one of the children—created a personal linguistic portrait, revealing their individual experiences, affiliations and biographical language memories.

This early work laid the foundation for a method that would later grow far beyond its initial frame and transform into what we now call "Linguistic Living Spaces".

When we first began working with families in multilingual contexts, our goal was simple:

Could we represent the linguistic life of a whole family in one shared portrait?

At that time, our starting point was Brigitta Busch’s linguistic portrait — a powerful visual tool for exploring how individuals experience and feel their languages. We wondered whether we could adapt this idea to the family context. Our first thought was straightforward:

one sheet of paper, several figures, one collective family portrait.

However, the very first attempts made something clear:

even on the same page, the portraits remained deeply individual.

Languages clustered around their own bodies, their own histories, their own feelings. What we needed was not several people on one page, but a shared space that could hold the family as a unit.

And that is when we found the answer.

The Home as the Family’s Linguistic Nucleus

During our early discussions, we realised that the family’s “nucleus” — the centre around which daily language practices revolve — is not the individuals themselves, but the home.

It is in the home where languages meet, clash, merge, coexist, and change.

It is here that family members negotiate what language to pass on, when and how to use it, and what emotional value it carries.

So instead of multiple figures on one sheet, we drew a house.

This simple shift — from bodies to space — changed everything.

Participants began filling the house with languages:

in rooms, doorways, windows, gardens, corners, and symbolic spaces. They did not only depict the languages they actively used, but also those that surrounded them:

the neighbours’ languages, the language of the kindergarten, the language of a parent’s workplace, the languages of the street, the building, the media they consumed.

The house became a living linguistic ecosystem.

Two Case Studies That Changed Everything

Our first applications of this method took place with two families in multilingual settings in Austria and Switzerland. We combined:

individual linguistic portraits,

a collaboratively created “family house”, and

narrative interviews about the drawings.

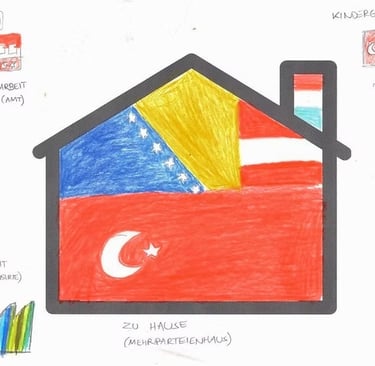

Family 1, from Bautz, Anabel; Habitzel, Julian; Hanisch, Antonia; Koblitz, Carola; Lechner, Hannah; 2022. Family Language Poli. (2022)

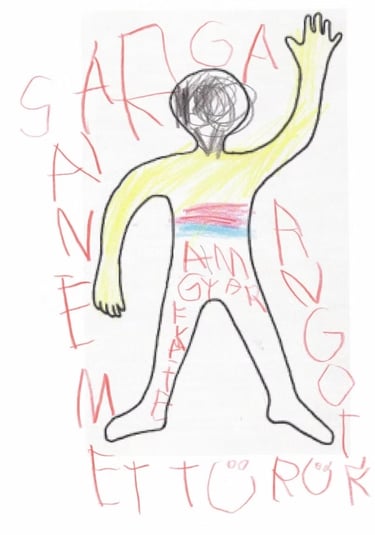

Familie 1, Familienportrait. Sprachenportrait Kind Sprachenportrait Mama Sprachenportrait Papa

Family 2, from Bautz, Anabel; Habitzel, Julian; Hanisch, Antonia; Koblitz, Carola; Lechner, Hannah; 2022. Family Language Poli. (2022)

Familie 2, Familienportrait Sprachenportrait Mama Sprachenportrait Papa

From the very beginning, the visual data revealed something important:

families portrayed not only the languages they speak, but the languages that inhabit their world.

We saw:

languages placed in particular rooms because of emotional meaning;

languages appearing only in the spaces of work, bureaucracy, or school;

heritage languages represented as corridors connecting past and present;

surrounding languages sketched into windows, streets, labels, or balconies;

movement between spaces showing code-switching and daily multilingual practices.

The portraits captured language as spatial, situated, dynamic, and deeply affective.

They showed how families live in multilingual ecologies shaped by people, places, institutions, and memory — not just “competence in multiple languages.”

Languages as Functions in Everyday Life

Through these early experiments, we also noticed that families represented languages by their functions:

the language of work

the language of the child’s kindergarten

the language of bureaucracy

the language of media, books, and music

the safe “home language”

the language used only with grandparents

languages of the surrounding community

These functional inscriptions demonstrated that multilingualism is not static, but relational and purposeful — helping us see language as something lived and enacted in social spaces.

Realising the Method’s Potential

After analysing the two case studies, it became undeniable:

this new visual-spatial approach had strong explanatory power.

It helped us:

study language practices and family decision-making,

understand how languages are emotionally positioned,

observe interactions between internal and external linguistic environments,

examine symbolic and ideological hierarchies in a household,

and analyse how people experience being surrounded by languages they do not necessarily speak.

At this moment, we recognised that the method’s potential reached far beyond family language policy.

Its spatial and affective lens could be applied to:

heritage language research

multilingual identity work

educational and didactic contexts

teacher training

community language projects

qualitative and arts-based linguistics research

These early insights laid the foundation for a new methodological approach.

Linguistic Living Spaces Was Born

What began as an adaptation of an existing visual tool developed into something distinct:

a way of understanding multilingualism as lived, embodied, spatial and affective.

By inviting participants to draw or build the spaces where their languages “live,” we do more than collect data,

we make multilingualism visible.

These first houses built with families were the seeds of what is now the Linguistic Living Spaces (LLS) method:

a visual, spatial and arts-based approach for exploring how people inhabit their linguistic worlds.

LLS continues to grow through workshops, empirical studies, and international training contexts. But its origin is rooted in something simple and powerful: listening to multilingual families and learning to see their languages not only as systems, but as spaces of life.

References and images copyright from:

Bautz, A. M., Habitzel, J., Hanisch, A. J., Koblitz, C., & Lechner, H. (2023, 8. März). Family Language Policies in einem “Minderheitenkontext”: Zwei Fallbeispiele (Research report - Course 160175 PS Minority Studies, Dr. Mi-Cha Flubacher, Winter Semester 2022/23). University of Vienna.

Bautz, Anabel; Habitzel, Julian; Hanisch, Antonia; Koblitz, Carola; Lechner, Hannah; 2022. Family Language Poli. (2022). Familiensprachpolitik und Familienzweisprachigkeit. https://familylanguagepoli2.wixsite.com/family-language-poli [Last seen 4. May 2025].

Familienportrait. Bautz, Habitzel, Hanisch, Koblitz, Lechner (2022)

Familienportrait. Bautz, Habitzel, Hanisch, Koblitz, Lechner (2022)